[Update in italics: May 3, 2012] After I wrote this post PLoS ONE published a paper that fits nicely with the points I was making.]

Beryl Benderly’s blog post over at Science Careers caught my eye yesterday because she mentions a 2008 report from the UK about the retention of women chemistry PhDs in academia. As expected, the women are moving away from academe. By the end of their PhDs only 12% of women want academic research careers in chemistry compared with 70% who are in the first year of the PhD. Those are compared with a drop from 60% to 21% for men. (A disclaimer: I write regularly for Science Careers, but I wasn’t involved in this blog post in any way.)

Beryl takes a positive spin on this data:

The figures are still way above the percentage of new Ph.D.s who have any realistic chance of landing a job on the tenure track (at least in the United States). Thinking about the welfare of the young scientists who have devoted many years to preparing for their careers and are about to begin them, it does not appear “alarming” to me that they have traded in their formerly unrealistic notion about the possibility of landing an academic post.

I’m not so positive based on my anecdotal experiences. As a female chemistry PhD who flew the academic coop immediately after graduation (more on that here, here, and here), I’m one of those safe people, someone who walked away from the bench and hasn’t looked back. So as soon as young PhDs hear my story, they often delve into their own questions about the research life. What do I often hear? Confusion, disillusionment, and questions about how they can use their science in productive ways. A realistic picture of their academic prospects is a first step, but I’m not sure that the awareness provides a bridge between their PhD and how they might use it in the workforce.

This particular report talks about the role of isolation in the choice to leave academia. If you’re in an academic setting and plotting a nontraditional career move, that decision often increases that feeling of isolation. So in some cases, a young scientist has to make their immediate professional social situation worse in order to make it better. So step one is often finding a mentor or a like-minded support system and learning new skills, but all while you’re trying to maintain a presence in your laboratory. That’s easier said than done.

I realize that young PhDs who are happy in academia are not seeking me out, so I probably have an unusually gloomy picture. But I don’t think the academic system has addressed how it can broaden the career skills of young PhDs and support skilled scientists who become interested in policy, business, law, or education. I recognize that building a satisfying career involves incredibly personal decisions, and no career counselor or academic department can map that out for you. But better support for career development could help more PhDs who opt out of academia or research feel like extensions of their scientific community rather than renegades.

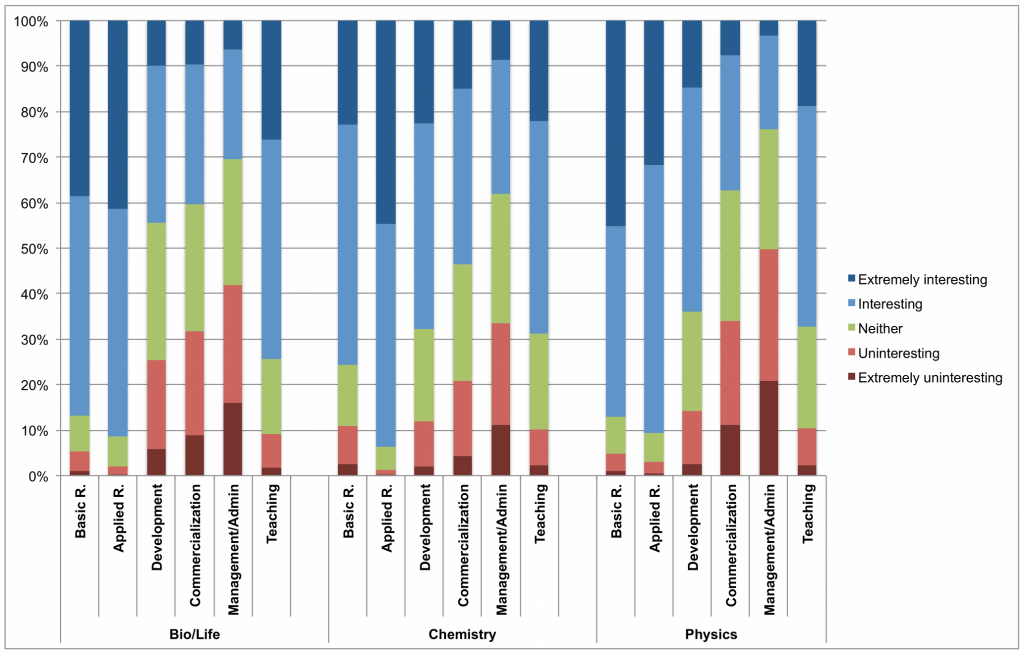

The PLoS ONE paper describes trends that I’ve noticed anecdotally. PhD students are less interested in the traditional academic research track by the end of their degrees. At the same time, they aren’t necessarily prepared for, interested in, or aware of the jobs that might be available that would capitalize on their skills. Faculty members seem to be relatively neutral about alternative paths, and what I’ve noticed talking with some young scientists is this general sense that they want to do “something else” but without any sense of what “something else” might look like.

And if you don’t want to take my word for it, here’s what the researchers have to say about the way that student interests, encouragement, and career opportunities aren’t lining up. (Emphasis is mine).

Second, respondents across all three major fields feel that their advisors and departments strongly encourage academic research careers while being less encouraging of other career paths. Such strong encouragement of academic careers may be dysfunctional if it exacerbates labor market imbalances or creates stress for students who feel that their career aspirations do not live up to the expectations of their advisors. In the context of prior findings that students feel well-informed about the characteristics of academic careers but less so about careers outside of academia [17], our results suggest that PhD programs should more actively provide information and training experiences that allow students to learn about a broader range of career options, including those that are currently less encouraged. Richer information and a more neutral stance by advisors and departments will likely improve career decision-making and has the potential to simultaneously improve labor market imbalances as well as future career satisfaction [23], [24]. Advisors’ apparent emphasis on encouraging academic careers does not necessarily reflect an intentional bias, however. Rather, it may reflect that advisors themselves chose an academic career and have less experience with other career options. Thus, administrators, policy makers, and professional associations may have to complement the career guidance students’ advisors and departments provide.

So let’s figure out how to bridge the disillusionment. I can’t think of a bigger waste of scientific talent than to have young researchers floundering because they don’t know how to bring their skills into a useful and productive career.

As a postscript, check out my fellow blogger Chemjobber, who doesn’t pull any punches about all things job- and chemistry-related.

There is some confusion here. The report referred to (The Chemistry PhD: the impact on women’s retention http://www.theukrc.org/files/useruploads/files/the_chemistry_phdwomensretention_tcm18-139215.pdf ) has only just been published, but builds on an earlier 2008 report. I’ve written about my own thoughts on the recent report here http://occamstypewriter.org/athenedonald/2012/03/27/is-or-was-your-phd-an-ordeal/. My impression is that in the UK, Chemistry is something of an outlier, something the earlier report showed by comparing the situation with Biochemistry.

Thanks for clearing up the date of the report (Is there a date listed somewhere? I couldn’t find it.) and for your comments. I’m wondering about the earlier comparison with biochemistry– did the biochemists identify more as life scientists than chemists (Did they have more in common with their colleagues in molecular biology?). What made their experiences different?

The chemistry/biochemistry report is here http://www.rsc.org/images/MolecularBiosciences08_tcm18-139859.pdf and suggests there are significant cultural differences

Thank you, Athene. I appreciate the added context.